History of Sunderland

Sunderland is a city of future living, but our community is proud of its past. From the foundations on which our city was built, to our ties to shipbuilding, collieries and the railway, Sunderland today is best known for its warm, welcoming people, its hard-working culture and its strive towards innovation and digital connectivity.

Discover our roots and what shaped Sunderland to become the diverse, well-known North East city it is today that welcomes people from all across the world each year...

Ancient History of Sunderland

Before Sunderland became a bustling city, it was one of three small settlements by the mouth of the River Wear on the North East coast of England. Excavations uncovered at St. Peter's Church in Monkwearmouth suggest that prior to these settlements, the earliest inhabitants of the region were Stone-Age hunter gatherers, and that Hastings Hill was a point of spiritual significance.

Following the Roman invasion, a group known as the Brigantes lived in the area. In 2021 Roman artefacts were even uncovered from the River Wear, suggesting evidence of a Roman Dam or Port in the Wear.

How Sunderland Got Its Name

It wasn't until the Middle Ages that Sunderland as we know it began to take shape...

The settlements on the River Wear are said to date back to 674 when King Ecgfrith of Northumbria granted land to Benedict Biscop - an Anglo-Saxon abbot - who went on to found Monkwearmouth Monastery.

This monastery - which is one of the oldest in Britain - became a major centre for learning, and had ties to Bede, a prolific writer, teacher throughout the Middle Ages, who was born in Wearmouth.

Biscop was also granted the land adjacent to the monastery on the south side of the river. By the late 8th century, Vikings had raided the coast and the monastery was later abandoned. The lands on the south side of the river were later granted to the Bishop of Durham in 930 and became known as Bishopwearmouth.

By 1100, this area included a fishing village which became known as 'Soender-land' - which means 'a land that is cut asunder' - separated or put to one side, in this case, by the river.

The name 'Sunderland' had increasingly replaced the term 'Wearmouth' by the 18th century, and is how our famous city is said to have got its name.

Sunderland's Industries and Exports

21st century Sunderland is home to countless new and diverse industries, but this has transformed significantly over the decades. Historically, Sunderland's biggest exports were ships, coal and salt.

Fishing was the main commercial activity in 'Soender-land', yet a charter in 1179 saw Sunderland develop as a port. By 1346, it became a site for shipbuilding by a merchant named Thomas Menville, and in 1396, coal became one of the town's main exports.

By 1589, notable landowners Robert Bowes and John Smith had a technique for making salt, which put Sunderland on the map and led to the creation of Bowes Quay. Using poor quality coal from the local coal pit at Offerton, they created salt by evaporating sea-water in large iron pans. The good quality coal was then shipped off to London and East Anglia. Between 2,000 and 3,000 tonnes of coal were exported in the year 1600 - this increased to 180,000 tonnes by 1680.

Other exports included;

Lime for use in fertiliser

Alum and copperas, for dye-ing

Rope-making (during the Georgian era)

Glassmaking

Pottery

Sunderland's Shipbuilding and Coal Mining Heritage

Several events can be tied to Sunderland becoming a booming centre for shipbuilding and coal mining both during and leading up to the Industrial Revolution. Some of the most notable events were;

A 1634 charter was granted to Sunderland by Bishop Thomas Morton, which saw a mayor and twelve alderman appointed as well as a common council for the town

The North was captured by parliament in 1644 following the Civil War

A Parliament blockade on the River Tyne crippled the coal trade of neighbouring city, Newcastle, allowing Sunderland's coal trade to flourish

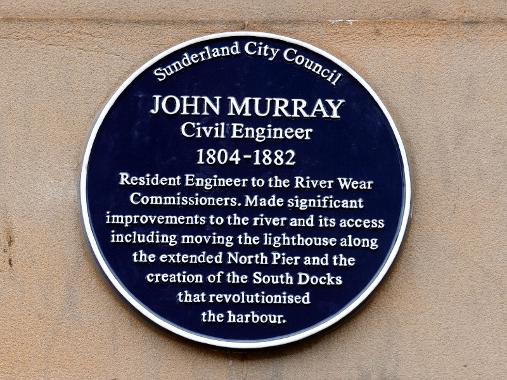

King Charles II's request for a pier and lighthouse to be built as part of the post-civil war restoration

Authorisation of tonnage duty of shipping, which led to shipbuilding on the River Wear

The River Wear Commission forming in 1717

As a result of these events, the riverscape was adapted to meet the needs of maritime trade and shipbuilding, with construction of piers and lighthouses. By the 18th century, the banks of the Wear were said to be studded with shipyards, building a number of warships and sailing ships. By 1788, Sunderland was Britain's fourth largest port and a leading coal exporter.

Did you know that the world's first steam dredger was also built in Sunderland in 1796 and put to work the following year? By 1815, Sunderland was 'the leading shipbuilding port for wooden trading vessels' and between 1846 and 1854, almost a third of the UK's ships were built in Sunderland.

As for coal mining, collieries with shallow 'bell' pits were commonplace by the 1600s to tap into the coal source that lay beneath the land, however by the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, new technology had allowed for deeper mines, unearthing precious coal vein that would continue to fuel Sunderland's coal trade. Allegedly, one Royal Commission report claimed that the Monkwearmouth Pit was the deepest coal mine in the world!

Sunderland Helps Give Birth to the Railway

In 1822, Hetton Colliery Railway was opened to link collieries with staiths on the riverside at Bishopwearmouth. Here, coal was delivered directly into waiting ships.

Prolific North East figure George Stephenson had engineered the railway, and this route became the first in the world to be operated without animal power. Similar railway links were established to Lambton Staithes and Seaham Harbour.

Sunderland in Wartime

By the early 20th century, Sunderland had become a bustling town with a tram service, concert halls, shops, businesses, parks and more.

Yet its exports, transport links and resources made it a prime target during both world wars. During WWI there was a notable increase in shipbuilding, which led to the Monkwearmouth area being bombed in 1916. While many shipyards had closed before WWII, Sunderland also remained a key target in WWII, with homes, businesses and parts of the town devastated by the German Luftwaffe.

While this led to more houses being built in the region, coal mining and shipbuilding sadly continued to decline. Sunderland's shipbuilding ended in 1988, and coal mining in 1993. This however signalled a new dawn for Sunderland, and development of new industries that would redefine and regenerate the region.

Sunderland Becomes a City

Despite its long history, Sunderland didn't become a recognised city until 1992, on the 40th anniversary of Queen Elizabeth II's ascension to the British throne.

Prior to this it had been considered a township. An Act of Parliament in 1809 was passed to create an Improvement Commission for Sunderland. By 1830, Sunderland had an Exchange Building which served - among other things- as a town hall, as well as a police force and gas lighting across much of the main town.

An outbreak of cholera in 1831 later led to the three parishes that acted as local government, coming together as the Borough of Sunderland in 1835.

To honour Sunderland's roots, St Benedict Biscop was named as Sunderland's patron saint when it became a city.

What's Sunderland Like Today?

Sunderland has been transforming and evolving into the vibrant, dynamic city it is today for the best part of the last 80 years. Sunderland today is a centre for electronic, chemical and paper industries as well as motor manufacturing. In 1986, Japanese car manufacturers opened Nissan Motor Manufacturing UK factory in Washington, which remains the UK's largest car factory.

Throughout the 1990s, the banks of the Wear were also regenerated with housing, businesses and retailers, while the creation of the National Glass Centre and University of Sunderland has played a big part in redefining Sunderland's cultural landscape.

Sunderland's football club Sunderland A.F.C has additionally continued to be a big part of our city's heritage, while the number of famous names from the region (including Bryan Ferry, James Bolam, George Clarke and Lauren Laverne, to name a few), continue to build Sunderland's reputation as a North East powerhouse of innovation, business and creativity.

Named the best city to live and work in 2018, and Smart City of the Year in 2020, Sunderland is a future focussed, digitally connected city that respects and cherishes its roots.

Many historic sites and buildings remain such as the Holy Trinity Church, the 14th century built Hylton Castle and the iconic Penshaw Monument, as well as hints of our industrial heritage which can be found in the town centre, riverside and nearby beaches. Each gives a glimpse into Sunderland's colourful past, and serves as a reminder of the story that shaped our city.

Five Facts about Sunderland

Sunderland's Aquatic centre contains the only Olympic size swimming pool between Leeds and Edinburgh

50% of the city centre is green space

The term 'Mackem' is said to either derive from the 'Blue Macs' - the name of the Scottish army barracked in Sunderland during the English Civil War. Another source suggests the term came from rival shipbuilders in the region who used the phrase 'Mak'em an Tak'em' as a reference to ships being taken from Sunderland.

Sunderland man Charles Whilems supposedly survived the sinking of the Titanic

Sunderland was said to have inspired Lewis Carroll's famous novel 'Alice in Wonderland', where he spent much of his childhood

As our city continues to grow, the story of Sunderland continues...

Don't just take our word for it, explore Sunderlands history for yourself using the Magical History Tour app, read below to find out more